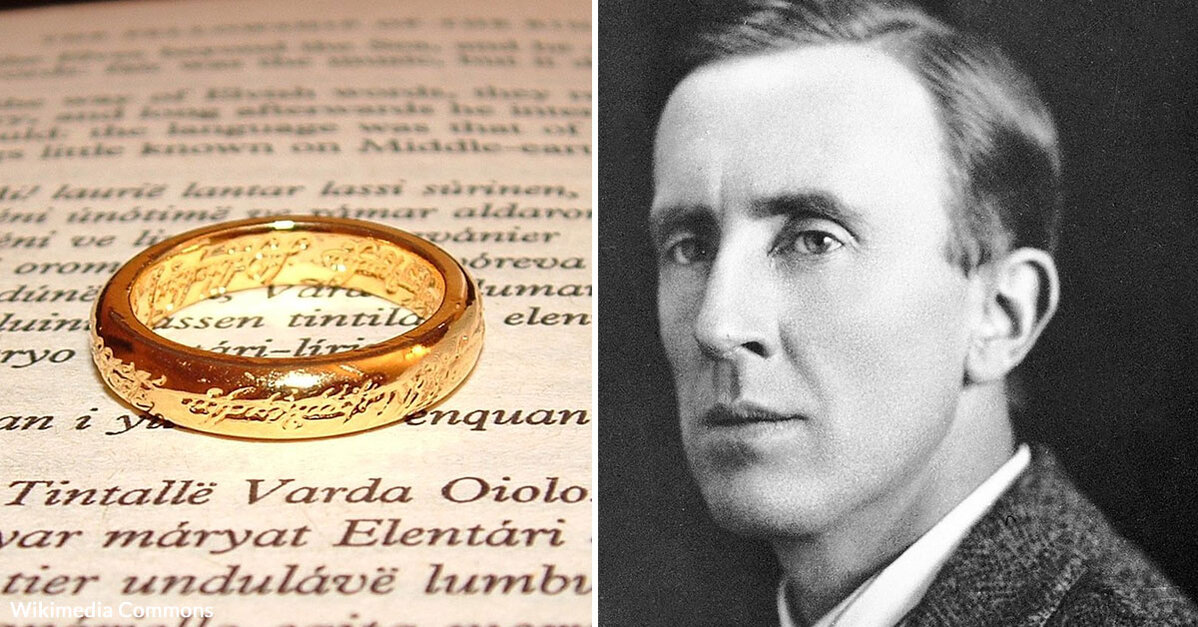

How WWI Shaped ‘Lord Of The Rings’ Author J.R.R. Tolkien

In the 1930s and 40s a group of writers and Oxford University professors used to meet regularly at a local pub in the university town of Oxford. They called themselves “The Inklings” and came together there because they all shared an abiding interest in literature and the power of narrative, that is, story-telling, particularly through the writing of fantasy, to reveal truths and universal human values. C.S. Lewis was one of the Inklings, as was John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, who we know better as J.R.R. Tolkien the masterful writer of the epic fantasy, The Lord of The Rings.

Tolkien shared another thing with C.S. Lewis as well, in that he too was a combat veteran of the Great War, WWI. Tolkien was a 2nd Lt. with the 11th Lancaster Fusiliers serving as the battalion Signal Officer. His greatest known work is, of course, The Lord of the Rings. This majestic fantasy that has captured the imagination of young and old since it was published in July 1954, is a masterful tale of a great struggle. Indeed, it is a book about war, all out, world engulfing, desperate war, that pits a coalition of beleaguered races of humans and elves, dwarfs, hobbits, etc. against a seemingly overwhelming, powerful, implacable, cruel and violent force bent on bringing the whole of Middle-earth under its rule.

The Lord of the Rings was born out of war. From July to October of 1916, Tolkien was in the trenches with his Lancaster Fusiliers at the Somme. Indeed, he lost two of his best friends who were killed in action there. The horror of this battle can be seen in its casualty counts. The casualties numbered over 1 million, including more than 300,000 killed in action. British forces alone suffered 420,000 casualties, including 125,000 deaths. Tolkien would be among those casualties being invalided back to England, suffering from what was called “trench fever,” a louse-borne disease. It does not take a great deal of imagination to think what the living conditions were like in those trenches, or the health issues that would arise from such conditions. Tolkien’s Lord of The Rings battles and the fact of war that occupies a central role in the tale, were shaped by this experience.

You might be able to imagine, too, that trench warfare was not a 24/7 reality. Like all combat, it was often 90% boredom interrupted by 10% of abject terror and destruction. Tolkien, in those times of boredom, in between his duties as a signal officer, was writing with his pen on scraps of paper, sometimes in grimy canteens, or in bell-tents along the trenches under candle light, even in dugouts under shell fire. It was there that he began laying out the foundational narrative that would eventually become Middle-earth.

Tolkien grew up, like most English kids, reading the Anglo-Saxon myths about Beowulf and the poems of the Wanderer, fairy tales, and vignettes concerning gnomes and sprites and elf-like creatures. When he was evacuated back to England, recovering from the effects of the trench fever, he wrote out the haunting epic of Gondolin, in which a city of high culture is destroyed by a nightmarish Army. More stories followed that began to shape a world that was far larger than the fairy tales of his youth, eventually becoming the grand myth of Middle-earth, which would be published under the name “Silmarillion” four years after his death in 1977.

It is clear that Tolkien’s experience of war was the catalyst for his “The Lord of The Rings.” It caused him to write a collection of stories that were unlike anything the world had seen before. Tolkien said of the book, “The mythology and languages first began to take shape during the 1914-1918 War. The kernel of the mythology…arose from a small woodland glade filled with hemlocks near Roos on the Holderness Peninsula to which I occasionally went when free from regimental duties while in the Humber garrison.

You may remember a scene in the book The Lord of The Rings, and in the movie, where the small group of hobbits that accompany Frodo, including Samwise Gamgee, are moving through a swampy quagmire on their way to return the mysterious and powerful ring to where it came from.

Sam falls into the muck…”and came heavily on his hands, which sank deep into sticky ooze, so that his face was brought close to the surface of the dark mere…For a moment the water below him looked like some window, glazed with grimy glass, through which he was peering. Wrenching his hands out of the bog, he sprang back with a cry, ‘There are dead things, dead faces in the water. Dead faces!”

This image, we can imagine, came right out of some of the nightmarish sights that Tolkien experienced in the trenches at the Somme.

Tolkien would live to see the rise of Germany again and the even more horrifying realities of WWII. In 1944, a week before the invasion of Normandy, he would write the following: “Romance has grown out of allegory and its wars are still derived from the ‘inner war’ of allegory in which good is on one side and various modes of badness on the other.”

Then this, “In real (exterior) life men are on both sides.”

This is a powerful insight for all of us to contemplate. War is not, as in the typical romance allegory, an affair pitting objectively pure good and evil against one another. The reality is that war is not an allegory. It is not an “allegory” for the inner struggle of conscience we all know and experience. Real War is no allegory. The reality is that war always arises from human failure, human failure on the part of all involved.

Tolkien’s “The Lord of The Rings was published nine years after WWII. It is a mythic war of epic grandeur and certainly is about the great struggle between the moral good and evil, but his characters reveal that this struggle isn’t always so clear. The “good” characters in The Lord of The Rings, from Frodo, to Aragorn, all face their inner struggle, the temptations to go to the dark side, so to speak. And sometimes they do, if only temporarily and are brought back by the challenge and love and loyalty of one or more of the characters. This inner struggle is seen most stunningly in the character, Smeagol, a former Stoor Hobbit who has become Gollum, deeply tortured and corrupted by the power of the One Ring. We see in this schizophrenic, tortured soul, the very evocation of the individual conscience struggling with the difficulty of intense moral choice.

In 1956, Tolkien wrote in a letter, “I think the fairy story has its own mode of reflecting ‘truth’, different from allegory or (sustained) satire, or ‘realism’, and in some ways more powerful. I did not foresee that before the tale was published we should enter a dark age in which the technique of torture and description of personality would rival that of Mordor and the Ring and present us with the practical problem of honest men of good will broken down into apostates and traitors.”

For J.R.R. Tolkien, the WWI veteran, The Lord of The Rings is not an allegory but a war story. And, as in war, the characters who survive the horrors of the battlefield come away from it changed, and they come back to a world that has changed, that is not recognizable to them. Frodo Baggins returns to the Shire changed, and he sees it now as a grey, flat place, grim with greed and hardship, that either fails to understand his war experiences or is indifferent to them. He has his character, the wise Gandolf say, “Alas! There are some wounds that cannot be wholly cured.” And Frodo responds with, “I fein it may be so with mine. There is no going back. Though I may come to the Shire, it will not seem the same; for I shall not be the same. I’ve been too deeply hurt, Sam. I tried to save the Shire, and it has been saved, but not for me. It must often be so, Sam, when things are in danger: someone has to give them up, lose them, so that others may keep them.”

Tolkien’s The Lord of The Rings is not an allegory for WWI. It was born out of it, in spite of it. It is a complex investigation of war and trauma, nature and industrialization, comradeship and loss. But at its core are the virtues of humility, patient endurance, courage, as well as the great virtues of faith and hope and love. There is redemption, but not in the romantic sense. The Lord of The Rings represents the complexity of human reality. We are not perfect. There is real good and real evil and we are not strangers to either. The story is about our broken humanity, but it also reveals our “better angels” and makes us look at ourselves once again. Through the power of story, we can come to see and to recover our better nature, the nature of humility through which, with the aid of grace, the victory of good over evil, within and without, can come to be.